T.S.Eliot’s juvenilia display the influence of Victorian aestheticism, his studies at Harvard, especially the influence of Irving Babbitt’s lectures there, helped foster his repudiation of the Romantic forebears of turn – of – the – century poetics.

George Bornstein notes that “Keats, Shelley and Wordsworth became a sort of anti – Trinity for Eliot,” but by the end of the 1930s Eliot had reached a “general truce with Romanticism.” A generation later, he implied that his struggle to find his own poetic voice had provided him an ability to view with greater clarity authors whom he had earlier disdained.

Eliot’s equivocal relationship to Romanticism reflects the broader evolution of the Modernist – Symbolist movement from early nineteenth – roots, especially in its valuing of the polyvalent symbol and the organic nature of poetic form, a keystone of Coleridge’s critical legacy. In Eliot’s case, he inherited from Romanticism “a negative theology perfectly suited to a genealogical recuperation of literary history as rebellion and restoration. Eliot’s denials defend him against the negative capabilities of his ancestors and plant his own negative authority in of former laureates.”

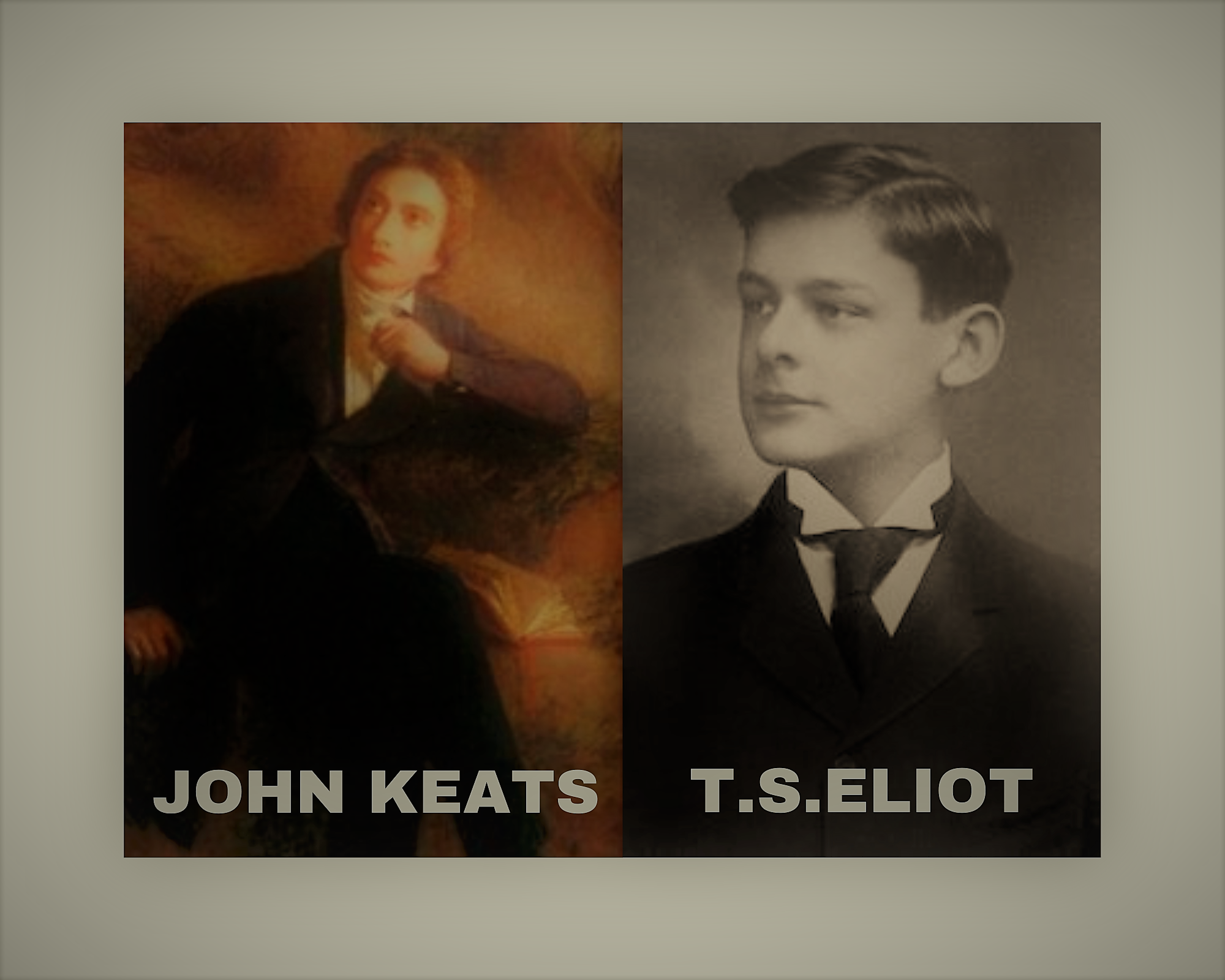

No predecessor could have modeled the virtues of negative capability for Eliot better than Keats, and there is ample evidence that he appropriated Keats’s poetry and critical pronouncements to a greater degree than his early rejection of the Romantics suggests.

Keats’s influence appears in “Eliot’s pre – 1910 juvenilia, such as ‘Before Morning’ and ‘On a Portrait’, where Keats, Rossetti and Swinburne presided over visions of ‘fresh flowers, withered flowers, flowers of dawn,’ and the apparition of ‘a pensive lamia in some wood – retreat, an immaterial fancy of one’s own.”

In The Waste Land, published twelve years afterwards, the line ‘out of the window spread’ seems to owe something to Keats’s ‘Ode to a Nightingale,’ and in the fourth of the ‘Five Finger Exercises’ of 1933, Eliot alludes to the ‘Ode on Melancholy’. His reference to the stillness of the Chinese jar in ‘Burnt Norton’ (1936) section of The Four Quartets also suggests “Keats’s Grecian urn – the static perfection acting as an unmoved mover upon the beholder.”

He ultimately came to share several fundamental tenets with Keats. Each believed that the English language as a poetic medium itself needed renewal; each looked for a way to embody meaning within the fact of a physical image; each praised the drama as offering a way of objectifying the poet’s experience; and each sought a poetic perception founded on dissociated sensibility – the meaning of Keats’s noted remark: “O for a Life of Sensations rather than of thoughts.”

These Keatsian links in Eliot’s work suggest the likelihood of an additional echo of Keats in Eliot’s essay on “The Metaphysical Poets”. Eliot praised the wit of the Metaphysicals for conveying a perception of experience which is simultaneously sensual and cerebral and which strikes with an unmistakable sense of its own uniqueness; such poets, said Eliot, “feel their thought as immediately as the odor of a rose”. It is an image Eliot could have recalled from Keats’s “The Eve of St. Agnes” at that instant in the poem when Porphyro conceives of a way to reach Madeline’s chamber: “sudden a thought came like a full – blown rose”. Porphyro here exhibits that fusion of thought and feeling which Eliot held to be central to the Metaphysical idiom, the balanced yet contrasting values that establish the themes of Keats’s narrative evoking the seemingly disparate yet conjoined levels of meaning within the Metaphysical conceit.

Eliot may have clarified his analysis of the Metaphysical stance by appropriating this Keatsian image for the complex interplay of reason and emotion he found in Donne and his successors. Although the idea of a dissociated sensibility has been traced to ears prior to the seventeenth century, Eliot enhances his articulation of this idea by alluding to a later work likely more familiar to his readers than the recently – popular Metaphysicals.

The unmistakable blending of the spiritual and the erotic within the “full – blown rose” also adds a Dantean resonance which would not have gone unnoticed by Eliot.

Eliot could have been drawn to Keats’s poem as well by the manner in which it reiterates that conjunction of apparently disparate ideas and values found in the Metaphysical conceit. An allusion to elements of Keats’s poetic design and meaning invites the possibility that Eliot’s blunt critique of the Romantics is by itself an incomplete picture of his complex response to their influence upon his early critical career.

To balance H.J.C Grierson’s perception, Eliot’s allusion thus calls to mind the one Romantic poet who had, however briefly, achieved that sensibility in his work. Eliot took Romantic emotion more seriously than had the Victorians, and his “anti – romanticism consisted in putting romantic feelings into practice.” Yet Moody contends that Eliot felt that the Romantics “should have suffered more, instead of wishing not to suffer” and poses Eliot in opposition to Keats: “Poets had listened to nightingales and been sad, or ‘half in love with easeful death’: he meant to live the reality behind the myth.” This seems unfair both to the visceral intensity of Keats’s letters and to Eliot himself, who knew that the great works of Keats’s Annus Mirabilis in 1819 was composed by a man who knew that he was dying. Eliot’s use of Keats’s rose to elucidate Donne in fact illuminates the complex equilibrium of reason and emotion which all three poets shared.